Clinical practice guidelines recommend psychological treatment interventions to target PTSD in veterans (International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 2009; The management of post-traumatic stress Working Group, 2004, 2010), and there a number of evidence-based treatments that have emerged from clinical trials and are recommended by agencies commissioned to meet the behavioral health needs of veterans experiencing combat and other trauma-related forms of distress. For example, in 2010, the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (DOVA) and the Department of Defense (DoD) assembled a workgroup to establish practice guidelines for treating PTSD in veterans and found exposure-based therapies, cognitive-based therapies, stress inoculation training, and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) to be “A-level” treatments for veterans with PTSD (The management of post-traumatic stress Working Group, 2010). Moreover, the DOVA website specifically names Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), Prolonged Exposure (PE) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) as “effective treatments for PTSD” (https://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/treatment/therapy-med/index.asp), and veterans have seemingly done well by receiving these types of recommended psychotherapies throughout the years (Kitchner et al., 2012) –or have they? A 2012 Congressional Budget Office study suggests that 78% of veterans with PTSD who received care from the Veteran’s Health Administration continue engagement with evidence-based trauma therapies, like PE and CPT, after four years of receiving an initial diagnosis of PTSD (Congress of United States, 2012). What is more, the National Center for PTSD reports that some veterans may never be free of trauma-related symptoms (https://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/index.asp).

These facts are troubling and highlight the need for a critical examination of first-line PTSD treatments for veterans. In other words, veterans who are receiving the “best we have” in trauma treatment and continue to require help for their symptoms begs a number of serious questions such as: What, if anything, is missing from first-line PTSD treatments for veterans? Is the individualistic nature of evidence-based treatments for PTSD limiting recovery and the achievement of resilience? Can the individualistic nature of first-line PTSD therapies be augmented to meet a broader spectrum of veterans’ psychosocial needs? If so, how?

In an attempt to answer these questions, the author will argue that there are a number of core treatment elements missing from available “gold standard” interventions for veterans with PTSD; elements that, if included within existing evidence-based models of PTSD treatment, could have a positive effect upon treatment outcomes for veterans regardless of which evidence-based trauma treatment they receive.

The author posits that one such missing element is the basic consideration of the relationship between veterans and their families by those offering trauma treatment. Although scant, there are enough empirical studies to argue the importance of considering the relationship between veterans and their families when deciding which therapeutic elements to include within evidence-based PTSD treatments for this esteemed population.

That said, what follows is a description of the structure of a family therapy session the author has designed to demonstrate how family therapy can become an essential component of evidence-based PTSD treatment for veterans like CPT:

Session 1

INTRODUCTION TO FAMILY THERAPY FOR PTSD

Summary of Session Content

Goals:

• The family will understand the treatment rationale for pairing family therapy with the veteran’s individual EBP sessions.

• The family will gain a basic understanding of the symptoms of PTSD.

• The family will gain a fundamental understanding of the ways in which PTSD symptoms can, and often do, become expressed within family relationships.

• Family members will learn the ways in which the family functions as a social system.

• The family will experience a general sense of ease and growing sense of trust with the family therapist.

Key Intervention:

1. Psychoeducation. One of the keys to the success of this first family session is the therapist’s ability to effectively explain the concept of systems theory. In practical terms, the family therapist’s task here is to aptly explain how the family operates as an “emotional whole” despite each of its individual members seemingly acting on their own accord. How is information this relevant to the family’s recovery from PTSD? If the veteran and his or her family members can gain a basic understanding of how all social systems operate–including family systems–then family members will, at the least, be better equipped to consider the important role each person plays in the maintenance and resolution of the presenting family problems, including those associated with PTSD. You might say that this initial conversation with the family will set the foundation for the entire course of family therapy for PTSD.

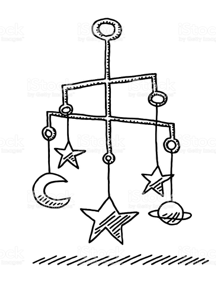

Moreover, to instill a clear understanding of how family systems function, the family therapist may use the following visual aid during the session to physically demonstrate how all family members may react to changes in another family member when they become clinically affected by PTSD:

Figure 1

Child’s Mobile

During the therapist’s explanation of the family as a system, he or she may use an actual child’s mobile and physically strike the lowest hanging mobile piece (in this case the large star) to demonstrate how, not only the large star, but the rest of the mobile pieces (the crescent moon, Pluto-shaped planet, etc.) are propelled off of their normal axis by the sheer force of the therapist’s hand. “Like the child’s mobile struck by an outside force, every family member is affected when one of its members experiences PTSD symptoms,” the therapist might say.

If more appropriate, the therapist might rather use the metaphor of a flying formation of military jets; for instance, if the family does not have any children or if the therapist believes that the image of the child’s mobile may, in any way, appear infantilizing to the veteran and/or his or her family.

“One jet pilot’s slightest move off course affects the course of the other pilots,” the therapist might alternatively say.

Framing the Family Solution

At the end of the first family session, the therapist would encapsulate the content of what was communicated throughout the hour by

making a summarizing statement that continues to frame the solution as a collective effort:

During the next few weeks in family therapy, we will be considering the problem of PTSD to be everyone’s; therefore, the focus of therapy will be working with everyone to examine your ways of communicating with one another; to help you become more aware of the ways in which each person may be contributing to the family’s problem with PTSD and working to improve it. As your family therapist, I will be offering you the opportunity to learn new skills to use in your family that you may find helpful. I will also be asking you to help me find new ways to help you help one another. Everyone will be asked to improve your relationship with yourself and with every family member. The benefit of doing this work may be that you feel more connected to members of your family; perhaps because you understand them just a little bit more. Whatever the outcome of our work together, I am confident that the time we spend together will be worthwhile!

There are many theoretical reasons to expect that adding family therapy to existing evidence-based PTSD treatments for veterans will significantly reduce PTSD symptoms while meeting the comprehensive mental health needs of veterans. The premise that mental health symptoms can be socially improved is firmly based upon decades of family therapy practice as well as research with veterans who have seen improvements in PTSD by engaging in systems-based PTSD treatments similar to family therapy.

In summary, the author proposes that existing evidence-based PTSD treatments for veterans is insufficient to treat the complex nature of veterans who are actively engaged in relationships with their families and romantic partners. Existing evidence-based PTSD treatments do nothing to address these transactional relationships, which may be prolonging or complicating recovery from trauma symptoms. And, while treatment of family and couples has been identified as a potential means of enhancing the effectiveness of treatment for veterans (Sherman et al., 2005), there are currently no evidence-based PTSD for veterans that provide opportunities for partners and family members to fundamentally contribute to symptom improvements; therefore, the author would argue that family therapy should be included in trauma treatment for veterans unless there it is contraindicated due to risk of physical or psychological harm.

References available upon request.

Written by Tony Madril, LCSW, BCD

Speak Your Mind